Columbia River Wild Steelhead Limbo - Going Lower than the Previous Lowest Return Since {1943} 2021

2023 Columbia River Preseason Summer Steelhead Run Forecast Lowest Ever

Agency Fishery Plans Are Not Aimed to Rebuild and Recover Wild Steelhead

By David Moskowitz

The pre-season forecast for summer steelhead passing Bonneville Dam from April 1 through October 31 is predicted to be fewer than 68,000 adult hatchery and wild fish. While it is a pre-season forecast, it is the lowest preseason forecast ever, and lower than the previous actual lowest Columbia River steelhead return in 2021.

Forecasting accuracy has been wildly variable. In 2021, the pre-season forecast was nearly 100,000 steelhead while the actual run totaled about 70,000 hatchery and wild fish with wild steelhead returns fewer than 25,000 fish – a 30% over-prediction.

The 2022 Columbia River Return was predicted to be about 100,000 total steelhead, and nearly 124,000 total steelhead passed Bonneville – a 24% under-prediction - to the positive – but again demonstrating the variability and lack of accuracy.

Wild fish totaled nearly 30,000 adults but as many as 15% of these unmarked steelhead are actually unclipped hatchery-origin fish – and many others may be feral hatchery fish resulting from Hatchery x Hatchery or Hatchery x Wild mating, which also further depress productivity of wild fish.

The number of wild steelhead predicted to pass over Bonneville Dam in 2023 is less than 21,000 fish, for the entire Columbia and Snake River Basin.

The 2023 wild steelhead forecast demands an open and careful review of the regulatory scheme in place for 2023. North of Falcon mainstem fisheries are considered and adopted independent of tributary fisheries - but must be considered and assessed in conjunction with tributary fisheries in Idaho, Washington, and Oregon.

The Conservation Angler examined the impact of the extraordinary regulations put in place in 2021 and 2022, and it was clear that the reduction in angler effort and steelhead encounters made a difference for wild fish reaching their spawning ground in greater numbers and in better shape.

However, grave concern exists with Oregon and Washington’s recreational fishery frameworks now in place – as they are reliant on wild steelhead return estimations from the 2022-23 spawning season (still underway) – because they will result in open seasons that began in May – at a time when wild fish often make up the majority of the early steelhead return. Based on the predicted return in 2023, sport steelhead seasons will close in tributaries when the majority of the hatchery fish return.

What is the scientific justification for 1) allowing early fisheries that will impact the depressed wild run more than the hatchery component; and 2) opening fisheries based on adult returns from the previous year? We urge reconsideration of the framework and we urge the Washington and Oregon Fish and Wildlife Commission to engage with the public on this issue now and not in July or August.

Oregon has taken proactive stances considering the wild steelhead decline, including:

• ODFW and then the Commission created the Thermal Angling Sanctuaries at the Deschutes in 2018, and then permanent rules at three cold water refugia by 2020.

Deschutes River Plume photo by J. Smith

• The Commission held a special meeting in August 2021 to address the unexpected decline in returning steelhead and some rivers were closed to steelhead angling.

• In early 2022, ODFW developed an outreach program with anglers to develop a series of Fishery Frameworks to provide more certainty for anglers – and protection for wild steelhead.

For these actions, TCA is grateful and it is clear that Oregon stands tall compared to neighboring states to the North and East. However, the Commission must continually re-examine its efforts.

Major Points of Contention with ODFW’s Deschutes Fishery Framework

1. Managing to Critical Abundance does not meet the Precautionary Principle

ODFW needs to develop fishery targets, rather than rely on CAT, which is a critical threshold in abundance that should be avoided at all costs, rather than be utilized as a minimum fishery target. ODFW either needs an escapement goal that establishes a target based on how many fish it takes to utilize available habitat or a tiered harvest rate structure, like in Skagit, where there is a minimum threshold beyond which there is no fishing. That is 4000 fish in the Skagit (watershed size is 2,370 square miles), not 625 fish. In either case, the minimum abundance target would be well above 625 fish for the Deschutes (watershed size is 10,000 square miles).

2. Using clipped versus unclipped fish does not account for unmarked hatchery-origin steelhead

The CAT of 625 means all those 625 fish are wild. As it stands now, some significant portion of returning Deschutes unclipped fish is either H x W hybrids or feral offspring of H x H spawning in nature. We have not seen any mention of what proportion of the forecasted wild population consists of those hybrid or feral fish, because they have much lower productivity than wild fish.

3. This is one of the best last remaining wild steelhead fisheries in the lower 48

The Deschutes River is one of the best last remaining wild steelhead fisheries in the lower 48 and ODFW probably makes more money off license sales from people fishing the Deschutes than any other Oregon stream above Bonneville (excluding mainstem Columbia). Considering its importance, ODFW needs to manage it more carefully. Currently, ODFW will allow fishing early in the upcoming season even though the forecast is expected to be dire and the worst on record. This doesn't make any logical sense. For example, if we had a salary of 30k last year, but forecasted a salary of only 15k for the upcoming year, we would be foolish to forecast expenditures under the presumption we would make 30k. That would result in huge loss of capital and eventually result in bankruptcy. The managers would be fired or the company would close. Despite having such knowledge, ODFW is forecasting to over-spend and exceed their biological budget. Why should anglers trust ODFW to manage our fish populations sustainably when they manage these irreplaceable wild steelhead based on extinction thresholds and are willing to overspend well beyond their predicted budget?

Deschutes Wild Steelhead photo by Riley Gyerko

4. There is little logical, biological, or ecological connection to opening a fishery on what is currently the lowest forecast for wild steelhead entering the Columbia River and currently beginning to pass over Bonneville Dam.

The number of steelhead passing over Sherars Falls in 2022 should have no bearing on whether ODFW should be managing more conservatively for a very low 2023 return. It simply does not make sense. ODFW states it is not managing based on the pre-season forecasts – so we ask why do the agencies even come up with preseason forecasts? The Oregon Framework is based on a correlation between last year’s return and the following year as steelhead returns often good or poor in a “clump” – that is bad and good years are often correlated, which in this case means another bad year is likely at hand.

Here is ODFW’s graphic supporting the correlation between past and present years:

Source: ODFW - The Dalles District Office

While prior years may help provide information about upcoming years, it is not a constant predictor, and there are commonly rapid swings in population size from one year to the next (from poor to good and vice versa) over time. If last year's run size always predicted next year’s run size, steelhead management would be simple. But as indicated in the model run above, ODFW’s explanation proves out at about 50% of the time – meaning that there is another 50% that ODFW’s model does not prove out. In other words, it is a coin toss decision.

A model that predicts accurately half the time doesn't provide enough evidence to open a fishery during a series of down years (since 2015) when wild steelhead are struggling to persist.

While ODFW uses real-time dam-passage data, the most effective way to use real-time data is to be conservative before opening a fishery and by monitoring dam counts in-season, then make a determination to open a fishery when the wild steelhead run size is actually large enough to absorb the impacts.

ODFW believes it can open the fishery for steelhead because its data shows that most encounters in the Deschutes occur after August 15th, and the framework provides opportunity early in the season but then allows for a closure if the return numbers are low so that they decrease the encounters when their data shows them to be most impactful.

While this may be true, our point is that this framework ignores careful consideration for the early fish that are mostly wild. ODFW’s use of the 50/50 model discussed above indicates that 25% of the wild fish are caught prior to Aug 15. Since run timing is heritable, those fish are likely different genetically than the later entering fish. Do they not deserve the same protection? Why is it ok to put part of the population at more risk? Further, because the early fish have longer residence times in the river, they are likely to be encountered more times than fish that spend less time in their tributary rivers. This shifting fishing intensity (earlier on earlier fish) could directionally select against the early timed fish and that would have a population impact. Particularly if the effects are as strong as noted in the recent ODFW research on angler versus trap caught steelhead in the Alsea (Johnson et al. 2023).

Last, they are not accounting for any sublethal impacts nor are they accounting for the potential genetic uniqueness of the early fish, which means the fishery could be having population level impacts if continued over time.

ODFW argues that there isn't directed sport harvest in the mainstem Columbia or in the tributaries, but there is indirect harvest via catch-and-release mortality (CnR). Thus, our point remains valid: Fish managers should not be using CAT thresholds as surrogates for fishery decisions. Because even harvest-focused fisheries do not rely on CAT or have escapement goals that are handful of fish away from being considered at increased risk of extinction.

Further, ODFW is not even attempting to account for potential sublethal impacts (for which there is already a large body of evidence on fishes), such as reduced reproductive success, reduced/altered movements, fungal infections (which can lead to reduced reproduction), etc. Additionally, CnR mortality is higher when water temperatures reach and exceed 68-70F. Is ODFW currently modeling the number of fish captured during the warm water events to ensure they have more accurate estimates of total CnR mortality? And what monitoring or research is being captured about the mortality risk for fish that are captured more than one time? How does ODFW account for that? In this context, by only considering direct CnR mortality (which ODFW only thinly does at the moment given their lack of modeling that includes potential for temperature and multiple encounters), ODFW conveniently ignores potential effects from high encounter rates during CnR, such as reduced reproductive success of fish that are CnR (particularly early fish that maybe caught multiple times) and eventual potential directional selection.

While prior years may help provide information about upcoming years, it is not a constant predictor, and there are commonly rapid swings in population size from one year to the next (from poor to good and vice versa) over time. If last year's run size always predicted next year’s run size, steelhead management would be simple. But as indicated in the model run above, ODFW’s explanation proves out at about 50% of the time – meaning that there is another 50% that ODFW’s model does not prove out. In other words, it is a coin toss decision.

A model that predicts accurately half the time doesn't provide enough evidence to open a fishery during a series of down years (since 2015) when wild steelhead are struggling to persist.

While ODFW uses real-time dam-passage data, the most effective way to use real-time data is to be conservative before opening a fishery and by monitoring dam counts in-season, then make a determination to open a fishery when the wild steelhead run size is actually large enough to absorb the impacts.

ODFW believes it can open the fishery for steelhead because its data shows that most encounters in the Deschutes occur after August 15th, and the framework provides opportunity early in the season but then allows for a closure if the return numbers are low so that they decrease the encounters when their data shows them to be most impactful.

While this may be true, our point is that this framework ignores careful consideration for the early fish that are mostly wild. ODFW’s use of the 50/50 model discussed above indicates that 25% of the wild fish are caught prior to Aug 15. Since run timing is heritable, those fish are likely different genetically than the later entering fish. Do they not deserve the same protection? Why is it ok to put part of the population at more risk? Further, because the early fish have longer residence times in the river, they are likely to be encountered more times than fish that spend less time in their tributary rivers. This shifting fishing intensity (earlier on earlier fish) could directionally select against the early timed fish and that would have a population impact. Particularly if the effects are as strong as noted in the recent ODFW research on angler versus trap caught steelhead in the Alsea (Johnson et al. 2023).

Last, they are not accounting for any sublethal impacts nor are they accounting for the potential genetic uniqueness of the early fish, which means the fishery could be having population level impacts if continued over time.

ODFW argues that there isn't directed sport harvest in the mainstem Columbia or in the tributaries, but there is indirect harvest via catch-and-release mortality (CnR). Thus, our point remains valid: Fish managers should not be using CAT thresholds as surrogates for fishery decisions. Because even harvest-focused fisheries do not rely on CAT or have escapement goals that are handful of fish away from being considered at increased risk of extinction.

Further, ODFW is not even attempting to account for potential sublethal impacts (for which there is already a large body of evidence on fishes), such as reduced reproductive success, reduced/altered movements, fungal infections (which can lead to reduced reproduction), etc. Additionally, CnR mortality is higher when water temperatures reach and exceed 68-70F. Is ODFW currently modeling the number of fish captured during the warm water events to ensure they have more accurate estimates of total CnR mortality? And what monitoring or research is being captured about the mortality risk for fish that are captured more than one time? How does ODFW account for that? In this context, by only considering direct CnR mortality (which ODFW only thinly does at the moment given their lack of modeling that includes potential for temperature and multiple encounters), ODFW conveniently ignores potential effects from high encounter rates during CnR, such as reduced reproductive success of fish that are CnR (particularly early fish that maybe caught multiple times) and eventual potential directional selection.

Deschutes Steelhead Fishing is a multi-generational activity

Here are the facts anglers should consider before fishing:

wild steelhead often comprise the larger component of the total early return April through July and at times, into early August.

Wild steelhead, even when outnumbered by hatchery steelhead, represent the majority of encounters in the sport fishery. They are more aggressive than hatchery fish and are caught more often even though they are outnumbered by hatchery fish in the river by the end of the season.

Anglers regularly catch wild steelhead in warm waters – increasing both the direct mortality risks but also the sublethal effects that diminish spawning productivity.

The Conservation Angler believes, after careful review, that the Deschutes River Fishery Framework is insufficiently conservative – especially considering the extremely low forecast. Managing down to the Critical Abundance Threshold (CAT) means we are over-spending our savings. The Framework provides a measure of certainty for anglers and managers -- but contributes nothing but uncertainty to the rebuilding and recovery of wild Columbia River Steelhead.

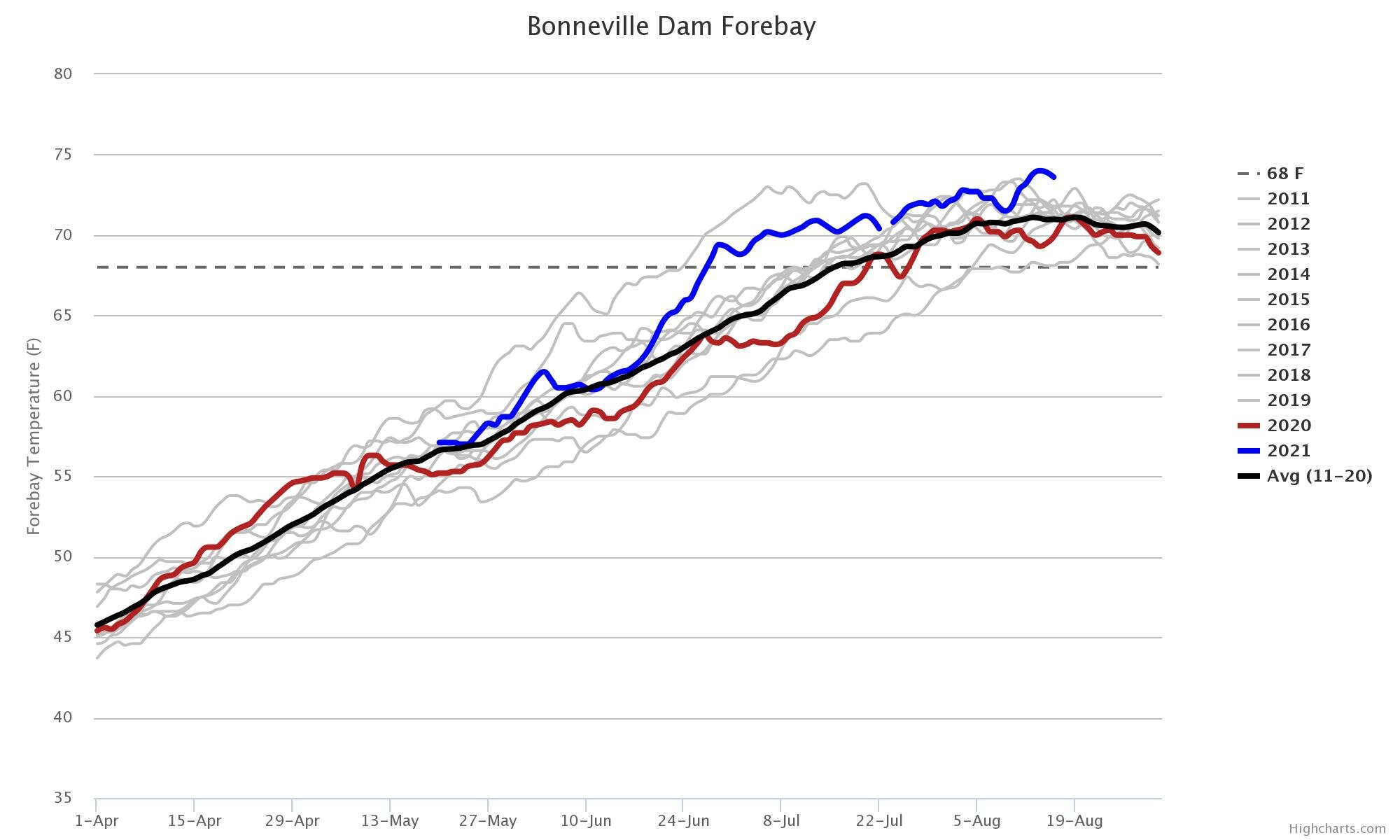

Comparing 2023 Wild Summer Steelhead returning to the Columbia River above Bonneville Dam Joint State Pre-season Forecast for Total Summer Steelhead Passage: April 1 thru August 1

v 67,800 combined hatchery and wild steelhead (H + W) expect to pass Bonneville Dam

v 20,700 total wild, unclipped steelhead expected to pass Bonneville Dam

We compare the current and past years to the current 10-year average (CTYA) steelhead passage (2013-2022) of 159,571 (combined hatchery & wild fish). The current 10-year average wild steelhead passage is 58,162 fish (includes unmarked hatchery fish). Comparing forecast passage with the CTYA from 2013-2022:

Ø The forecast 2023 return of combined wild and hatchery steelhead is 36% of the CTYA.

Ø The 2021 forecasted wild steelhead return was 34% of its CTYA (2011-2020).

Hatchery steelhead are forecast to outnumber wild steelhead by 47,100 fish. It is critical to know that up to 15% of the adipose-intact steelhead are hatchery-origin steelhead with an adipose intact upon release even though it is contrary to federal law.

To avoid the declining baseline syndrome, agencies should compare current run-size with a longer period or with a more productive period to be able to identify the overall loss of wild steelhead productivity and abundance.

We use the “best” 10-year average (BTYA) for steelhead, and with available data since 1984, the highest TYA occurred between 2001-2010 (410,370 H+W fish). The “best” 10-year average for wild steelhead also occurred from 2001-2010 (118,257 wild fish).

Thus, the current 2023 forecast of total hatchery and wild steelhead is 16.5% of the BTYA. The current 2023 forecast for wild steelhead run is 17.5 % of the BTYA.

Columbia River wild steelhead are not sustaining nor rebuilding their productivity, abundance, diversity, or spatial distribution by any measure.

Comparative Passage Graphs – Columbia River DART

Passage of Summer Steelhead – April 1 to June 13 (2023) – There are 55 more steelhead than in 2021. Current 2023 steelhead passage is 23% of earlier periods of steelhead abundance (2001-2010).

Source: Columbia River DART - 2023

Sport Fishing Issues in Idaho, Washington, and Oregon

• Anglers may use bait, barbed hooks, and treble hooks when steelhead fishing in rivers where wild fish must be released, though catch and release mortality rates for bait are higher than for artificial lures and flies.

• Anglers fishing in boats may continue to fish even when they have taken their limit, increasing the number of wild steelhead that are encountered and caught, adding to more lethal and sub-lethal encounters and loss of energetics for wild fish encountered in mark-select fisheries. The power of each boat is boosted by the “Party Boat” rule and to address encounter rates during low abundance, this rule should be rescinded. However, Idaho does not allow party boat fishing.

• Sport fishing on some tributary streams is allowed on other fish species but results in wild steelhead encounters and even targeted steelhead angling.

• Wild steelhead are caught more frequently in most Columbia and Snake River fisheries even though by season’s end, hatchery fish regularly outnumber wild fish in mainstem and tributary fisheries.

• Because most summer steelhead will not spawn until late winter through spring, their migratory behavior is less predictable and more likely to result in multiple angling encounters during their spawning migration. There is no analysis of the impact of multiple encounters of wild steelhead based on the simple creel survey database.

• Fishing for steelhead is permitted throughout staging and spawning periods between February and June on rivers such as the John Day, Umatilla, Grand Ronde, Clearwater, Snake and Salmon Rivers, increasing the likelihood of multiple angler encounters of the same wild fish and resulting in known loss of productivity and spawning success.

• Washington and Idaho permit night fishing for steelhead in multiple waters – enforcement is a major problem in these circumstances.

Meanwhile, Across the Columbia River

Washington State must revise its regulations to protect wild steelhead in tributaries and in cold water refugia.

First, WDFW’s Cold Water Refugia report presented to the WA Commission is incomplete and weak. Recent explanations about the use and effect of cold water refugia in Columbia River angling regulation setting was not based on any empirical data – simply best professional judgement. This is inadequate to address the wild steelhead conservation crisis.

Second, WDFW return to the 3-steelhead bag limit for hatchery steelhead has no justification. There is little data on encounter rates on wild fish in those fisheries - effort, encounter rate and mortality rate are all “assumed” from models with little if any real-time modeling, nor does the rule account for water temperature impacts for fish hooked, played, and released in warmer water.

The retention by Oregon and Washington of the “party boat rule” is a travesty. Allowing all anglers in a boat to continue to deploy their gear even when individuals have retained a limit adversely increases the number of encounters and mortality. It is also inconsistent with the angling rules that apply to bank anglers or single anglers in a boat.

Allowing fisheries to continue by merely prohibiting “retention” of steelhead is much different than a rule that prohibits altogether “angling for steelhead.”

Shooting fish in a barrel at Drano Lake

Finally, WDFW must not allow angling at night as enforcement is nearly impossible.

Tribal Steelhead Fishing

Columbia River Native American Tribes fish for steelhead for commercial, subsistence and ceremonial uses. The fish from platforms with traditional methods as well as with hook and line. Treaty Tribes also fish for salmon and steelhead using both set-nets anchored on the Columbia River bottom, as well as with drift gill nets.

In 2021, during the lowest steelhead return past Bonneville Dam in history, Columbia River Tribes reported harvesting over 3,400 hatchery and wild steelhead from their platform and gillnet fishing effort. This was about 5% of the total 2021 steelhead return – the second-lowest reported Tribal catch of steelhead based on records readily available.

Tribal gill net boat at Drano Lake

Management agencies have applied a number of conservation measures to non-tribal fisheries, but so far, none to the Treaty Tribes. One short-term measure that Oregon and Washington could take is to limit or prohibit the sale of wild steelhead currently allowed for commercial fish buyers or direct-to-customer fish sales.

Conclusion:

Fish management agencies are placing the burden of conservation on the wild steelhead in the Columbia River. The framework being applied only has a 50% chance of actually being the right fit to the circumstances, and even if the agencies have made the right heads or tails call, the conservation burden is increased on the early-returning wild steelhead – fish that might have the best chance of surviving the climate change impacts on their migratory and spawning pathway.

Sport fishing closures certainly reduce encounters but the implementation of limited entry fisheries or specific gear restrictions could also reduce encounters in a manner that is enforceable and provides opportunity to the non-tribal fishing community.

The Conservation Angler will never give up continuing to pursue remedies to this crisis for Columbia and Snake River Wild Steelhead.

What Can You Do to Protect Steelhead this Season?

Anglers willing to protect wild steelhead should take action themselves.

o Reduce your fishing effort

o If you fish, do not fish when the water temperatures are higher than 66F

o Use appropriate tackle to be able to land a wild steelhead quickly

o Use barbless single hooks and don’t fish with bait

o Fish a fly or lure with the bend of the hook removed to feel the tug

o Don’t take a wild fish out of the water when you land them

o Read about proper catch and release techniques at @Keepemwet

o Don’t buy tribal caught steelhead at your local market or thru fishing site sales

Send emails to Oregon and Washington officials demanding action.

Reduce hatchery production which depresses wild steelhead productivity

Mark all hatchery steelhead according to Federal Law

Pursue dam operation modifications and removals to help improve survival

Protect ALL cold water refugia

Prohibit angling in cold water refugia from July 1 to October 1

@MyODFW

@theWDFW

David Moskowitz is Executive Director of The Conservation Angler, one of The Osprey’s supporting partner organizations. This article is based on his testimony to the Oregon Fish and Wildlife Commission in April 2023. To learn more about The Conservation Angler visit: www.theconservationangler.org

Citations:

ODFW Deschutes Steelhead Fishery Framework:

Columbia River Fishing Regulations:

https://wdfw.wa.gov/fishing/management/north-falcon/summaries#columbia

EPA Cold Water Refugia Plan:

https://www.epa.gov/columbiariver/columbia-river-cold-water-refuges-plan